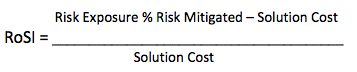

"At a high level, metrics are quantifiable measurements of some aspect of a system or enterprise. For an entity for which security is a meaningful concept, there are some identifiable attributes that collectively characterize the security of that entity. Further, a security metric (or combination of security metrics) is a quantitative measure of how much of that attribute the entity possesses. A security metric can be built from lower-level physical measures."1