Corporate security programs are as diverse as the corporations they serve. Each company, with its unique history, structure, and evolving needs, develops its security function in a distinct way. Often, this development is reactive, spurred by specific incidents like natural disasters, leading to the ad-hoc assignment of responsibilities for programs like disaster recovery or crisis management. And maybe the security department isn't in a position to take responsibility for one of those, so it's assigned elsewhere. This results in a fragmented landscape where the security department's purview can vary dramatically.

This inherent uniqueness poses significant challenges when attempting to benchmark one corporate security program against another. As revealed by the Security Executive Council’s (SEC) extensive research across over 400 security organizations over the past two decades, the very definition of "corporate security" differs wildly.

The Fragmented Landscape of Security Responsibility

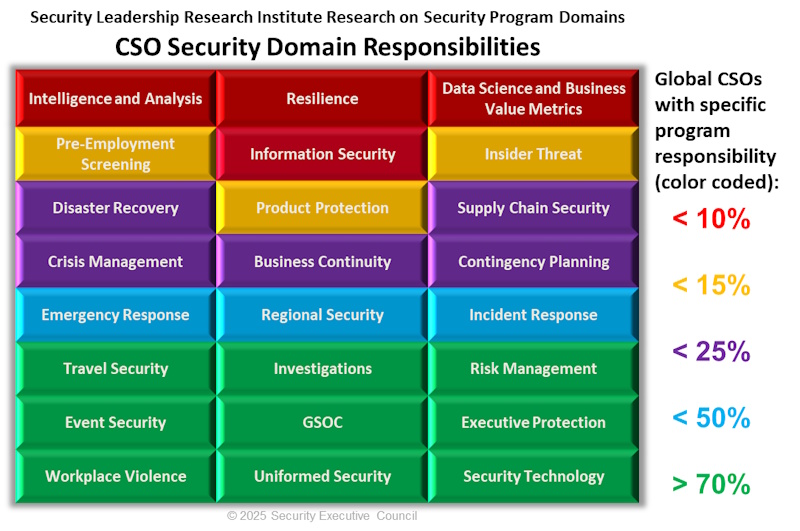

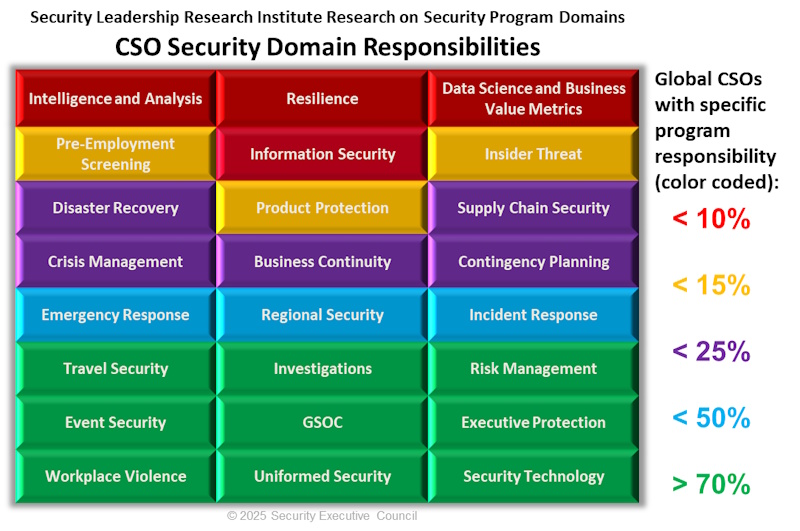

SEC's research has identified 24 key domains that commonly fall under the umbrella of corporate security. See figure below.

Figure 1 Analysis of SLRI research based on over 400 corporations self-reported program structure and responsibilities.

Figure 1 Analysis of SLRI research based on over 400 corporations self-reported program structure and responsibilities.

However, the analysis reveals a striking disparity in how these domains are distributed across organizations:

- Core Security (Green): Domains like physical security, investigations, and executive protection are frequently central to Security's responsibilities, appearing in over 70% of the security organizations studied.

- Shared Responsibility (Blue): Areas such as business continuity and emergency management are less consistently owned by security, falling under their purview in less than 50% of the companies surveyed.

- Limited Security Involvement (Purple, Orange, Red): Domains like supply chain security, product protection and information protection are even less likely to be the primary responsibility of corporate security, with ownership falling below 25%, 15%, and 10%, respectively.

Furthermore, the number of domains a security department is responsible for varies significantly. A staggering 70% of the 400 security programs studied had responsibility for only 5 to 10 of these 24 domains. In stark contrast, SEC has encountered few clients where the security function oversees all 24.

The Pitfalls of Blind Benchmarking

This vast diversity underscores the danger of superficial benchmarking. Comparing a security program responsible for only five domains with one managing all 24 is akin to comparing apples and oranges. The budget, headcount, organizational structure, and even the fundamental mission of these two departments will be drastically different.

Imagine trying to glean meaningful insights by comparing the budget of a security team focused solely on physical access and personnel security with one that also manages global supply chain security and intellectual property protection. The scale of responsibility directly correlates with the resources required.

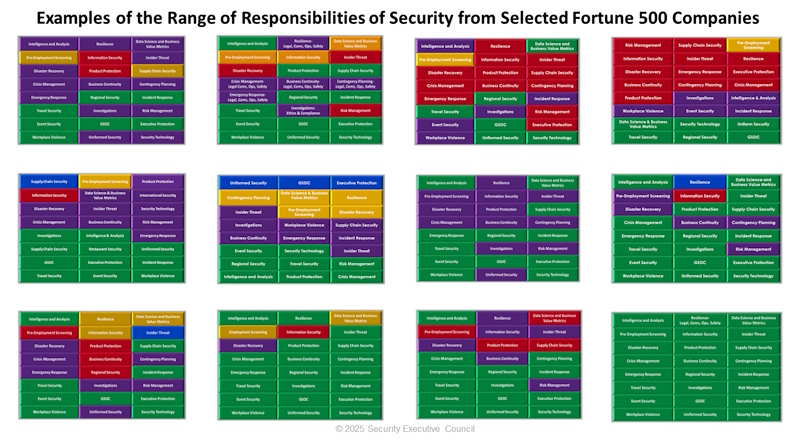

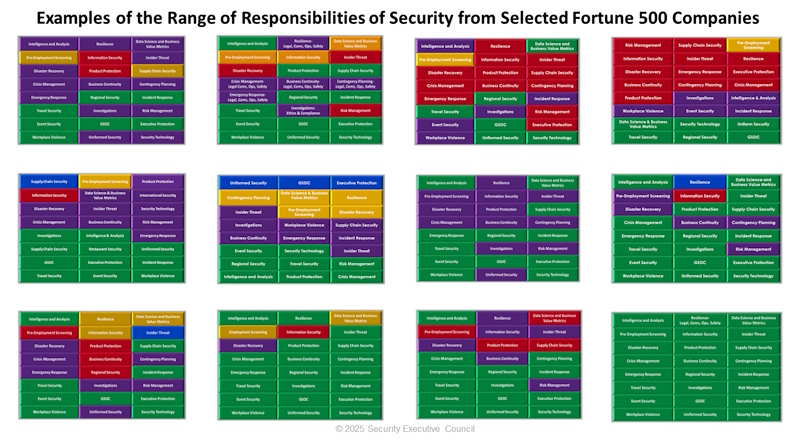

Figure 2: Examples showing the range of responsibilities of security from some of the fortune 500 companies participating in the research.

Figure 2: Examples showing the range of responsibilities of security from some of the fortune 500 companies participating in the research.

The chart above further illustrates this point, it shows twelve SEC clients with vastly different organizational responsibilities and, consequently, disparate budgets and resources. This image also emphasizes the varied nature of security's engagement with internal stakeholders – ranging from direct ownership to partnership, consultation, or even no involvement at all – there is clearly a lack of uniformity in what corporate America calls corporate security. This lack of uniformity makes direct comparison incredibly difficult and potentially misleading.

Figure 3: Definitions of Security Programs vary company by company. Programs listed were identified as most prevalent by research participating organizations.

Figure 3: Definitions of Security Programs vary company by company. Programs listed were identified as most prevalent by research participating organizations.

What You Need to Know Before You Benchmark

Before even considering benchmarking, a crucial first step is to gain a deep understanding of your own organization's unique security landscape. This involves:

- Mapping Domain Ownership: The most critical initial step is to clearly identify who within your organization is responsible for each of the 24 security domains. This includes understanding not just formal ownership but also the level of security's involvement – whether it is primary responsibility, partnership, consultation, or no involvement. Surprisingly, many organizations lack this fundamental clarity. Even hiring managers should be able to articulate security's role across these domains during the interview process.

- Understanding Your Role: Define the specific responsibilities and expectations placed upon the security function within the broader organizational context. This goes beyond the job description and delves into how security interacts with HR, Legal, IT, and other departments across all relevant domains.

- Analyzing Internal Stakeholder Expectations: Understand what other departments expect from the security function in areas where security does not have direct ownership. Do they expect security to possess specific skills in those areas, or is their involvement minimal?

Aligning Structure with Role, Not the Other Way Around

Instead of striving for a "perfect" security department based on external benchmarks, the focus should be on aligning the security function's structure with its defined roles and responsibilities within the unique organizational ecosystem. A "role-based program" is a better approach as it prioritizes understanding and fulfilling the specific security needs and expectations of the organization, rather than blindly adopting a generic organizational design.

Why Valuable Domains May Reside Elsewhere

A critical question the security community needs to ask is: why are often the most valuable domains, such as product protection, information protection, and supply chain security, not always assigned to corporate security? Several factors can contribute to this:

- Historical Development: As mentioned earlier, these responsibilities may have been assigned to other departments reactively as specific needs arise.

- Existing Expertise: Other departments, like R&D for product protection or IT for information protection, may possess perceived specialized knowledge.

- Organizational Silos: Lack of communication and collaboration between departments can lead to fragmented ownership.

Even in areas traditionally associated with security, like investigations, specialized investigation groups may exist outside of corporate security for specific purposes like fraud or product protection.

Context is King in Corporate Security

The key takeaway is that corporate security programs are highly context dependent. Benchmarking can be a valuable tool for gaining insights and identifying potential areas for improvement, but it must be approached with extreme caution. Without a thorough understanding of your own organization's unique distribution of security responsibilities and the underlying reasons for it, comparing your program to others can lead to flawed conclusions and misdirected efforts. The first and most crucial step is to map your internal security landscape and understand your role within it before looking externally. Only then can benchmarking provide meaningful and actionable insights.

Next Steps

The security roles and responsibilities data presented in this report was provided by the Security Leadership Research Institute (SLRI). This research arm of the Security Executive Council is specifically designed to offer actionable insights that empower security professionals. By participating in SLRI, security leaders can gain access to a growing pool of research that helps shape the future of informed, strategic security decision-making.

Find out more about SLRI here.

Download a PDF of this page below: